James John Neale looked up at the portrait of his father, that epitome of the Victorian Age, continuing to dominate all that he surveyed from his position hanging over the fireplace. George Neale II had been a hard taskmaster, but they got on much better now that James was able to monopolise the conversation – indeed it was rare these days to get any response at all. The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away.

Not that the exchanges were completely one-sided. Sometimes, late at night, as James smoked a post-prandial cigar in his study and swirled his brandy round in a snifter, he had the distinct and uncomfortable feeling that his father was watching him and, on one memorable occasion, a sidelong glance at the portrait caught his father raising an eyebrow at him in a most disdainful manner. That was the night James had decided to cut down on the brandy.

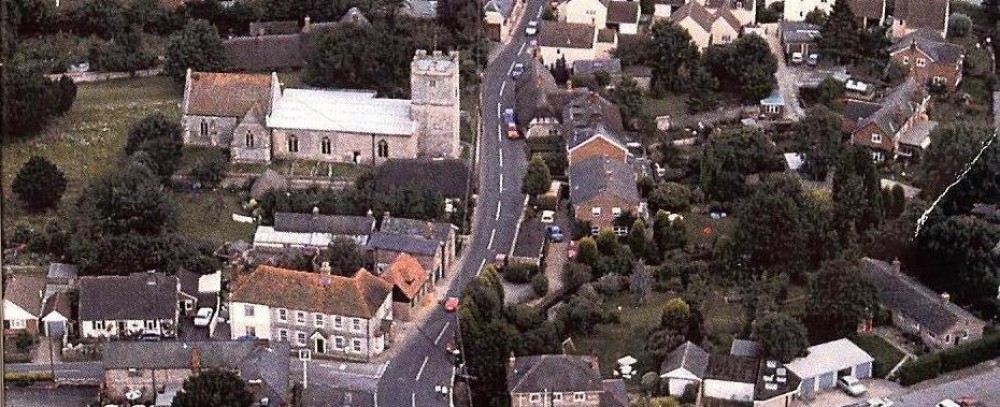

It was his grandfather, George Neale I, who had moved to St Mary Bourne from Dorset in the early nineteenth century, and set up shop as a carpenter and wheelwright.1 Either he had been able to bring a capital sum with him from Dorset, or his business prospered mightily, as he was able to buy the George Inn in the centre of the village (which had been going for at least 100 years, plot 54), which he put in his wife’s name. George and his wife lived, and had their carpenter’s shop, near the church in the Egbury Road (plot number 20 in the Tithe Map below, and they rented part of plot 23 behind as an orchard).

James never met his grandfather and had no recollection of his grandmother, who had died when he was only one year old. After George I’s death, Harriet Neale had continued the carpentry and wheelwright business right up until her own death twenty one years later, at the age of seventy-seven, with her unmarried daughter Ellen living with her and working as a dressmaker.

By 1861, her eldest son, George II, (the one in the portrait) had moved into his own house, set up as a grocer employing one man, and married the unfortunately named Olive Green (more amusing for her parents than for her, no doubt). James had been born at the end of 1860, the sixth and last child of his parents: he had an elder brother (inevitably called George) and four sisters.

By 1871, George II had branched out into farming and described himself as a ‘shopkeeper, wheelwright and occupier of 77 acres of land, employing two labourers and one boy’. He had also taken on the post office, as well as owning a grocer’s and a draper’s (the two were probably not in the same shop – it is hard to imagine buying cotton reels and cabbage together). And George III is described as a baker.

By 1878, George III has taken on Jamaica Farm, to the east of the village.

So far, so good. But then two things happened. George II died in September 1879 and the agricultural depression took firm hold. The History Blog explains it thus:

External as much as internal forces increasingly influenced the Victorian countryside.[2] The poor harvests and deep depression especially in the arable sector in the 1820s and 1830s[3] was followed by recovery as rising home markets took agriculture into a so-called ‘Golden Age’ from the late 1840s to the early 1870s.[4] The dominance of wheat production ended as grain prices collapsed under the flood of cheap imports from the New World after 1875. Free trade meant that British farmers could not respond. Markets for stock and dairy products and perishable cash and fruit crops benefited from rising real wages and growing demand, but they too experienced foreign competition with the development of refrigeration and canning after 1870. The agricultural depression of the late 1880s and 1890s was widespread and crippling. [5] It reflected the decline of agriculture’s share of national income from one-fifth in 1850 to one-twelfth by the 1980s.[6]

In settling George III into Jamaica Farm, it had no doubt been George II’s intention to settle his eldest son into a lucrative business, which would allow him to live in relative comfort and continue to build the Neale family fortunes. The habit of primogeniture dies hard in the British male bosom.

By allocating the shop(s) and the post office to the younger of his two sons, James John, George II had presumably intended to leave him adequately provided for, but not to the same standard (or with the same social prestige) as George III. But fate and international markets had, as it turned out, decreed otherwise.

Poor George III. He had not done too badly in the end, he moved to Charlton Manor Farm and spent the next forty years or so in some comfort, married Agnes Withers and had nine children. When he died in 1938, he was to leave

Poor George III. He had not done too badly in the end, he moved to Charlton Manor Farm and spent the next forty years or so in some comfort, married Agnes Withers and had nine children. When he died in 1938, he was to leave  a respectable but not huge sum of £5,000.

a respectable but not huge sum of £5,000.

And what of James John? Well, in 1911 he is listed as ‘Neale and Son, grocers, drapers, and sub-postmasters’. By 1920, he was to cross through the green baize door and be listed among the ‘Private Residents’ in Kelly’s Directory as the owner of Hilliers Lodge in Stoke.

No wonder George II raised a quizzical eyebrow at him from time to time.

1 George Neale the first died at the age of 45 and was buried in the churchyard of St Peter’s Church, St Mary Bourne, on 13 October 1840. A copy of his will (1841B/42) is held in the Hampshire Record Office; it gives his occupation as carpenter and wheelwright.

Pingback: Elizabeth Day Purver | St Mary Bourne Goes To War

Pingback: The Second Wave Of Reservists | St Mary Bourne Goes To War