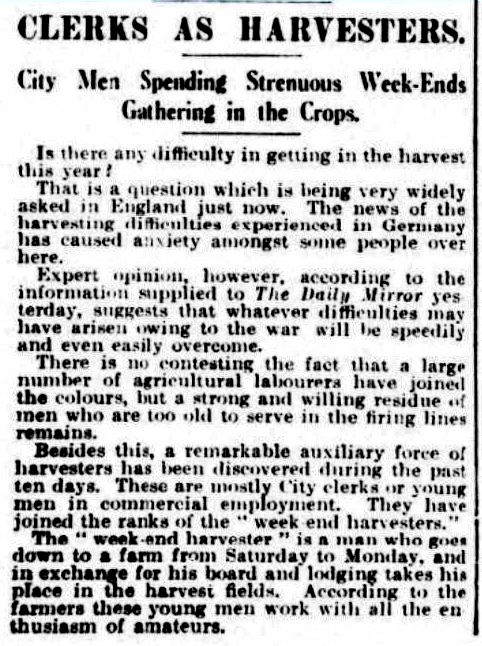

Goodness knows how The Daily Mirror had got hold of the story, but John Notley hoped that the first batch of Londoners he was getting on Friday evening would indeed have ‘all the enthusiasm of amateurs’. He certainly had plenty of work left for them to do, and plenty of acres for them to do it in.

Goodness knows how The Daily Mirror had got hold of the story, but John Notley hoped that the first batch of Londoners he was getting on Friday evening would indeed have ‘all the enthusiasm of amateurs’. He certainly had plenty of work left for them to do, and plenty of acres for them to do it in.

John and his son Charles had run Egbury Farm as the bailiff for Mr Rouyer when he owned Dunley Manor. And they had continued with Mr Francis Holman when he bought the Dunley estate in 1902.

© Copyright Graham Horn and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence via geograph.co.uk

They were a Dorset family originally, but like several others from the county had moved up to Hampshire in the 1890s when the economic difficulties in farming hit home and several farms became available at very reasonable prices. In Hurstbourne Tarrant, there was George Miles and in Ibthorpe John Bound, both also originally Dorset families.

A note on sources

The information about the Dunley estate and the Notleys is taken from 59A03/7 in the Hampshire Record Office. They also appear in the various trade directories.

The Daily Mirror was a popular daily newspaper and claimed that it had a “Certified circulation larger than that of any other Daily Picture Paper”. It was a tabloid rather than a broadsheet. It had a long standing relationship with the labour and trades union movement and was aimed at the middle and working class households.

It was one of the first dailies to introduce photographs to its pages and a quarter of the paper concentrated on photographs of the war and those associated with it. It cornered the market for the bizarre and aimed to amuse as well as to inform. It minimised its news content to a double page, leaving space for adverts on female interests, such as ‘Infant feeding’ and ‘Grey Hair’. Its Human Interest articles covered stories such as “ ‘Spiritualistic’ Quacks in War-time”, which told of Mediums, Crystal Gazers and Palmists being bombarded with female believers, worried about relatives at war.

It featured a political cartoon; adverts for clothing outlets, tobacco and food; short stories “Like all other Men” by Mark Allerton being one of many; ‘This Mornings Gossip’; a sport and entertainment page; ‘A thought for today’ and ‘In my Garden’ also featured regularly. It often featured Winston Churchill as he wrote a column in the ‘Sunday Pictorial’ for the Paper.